Blue and white collar: Identifying industries

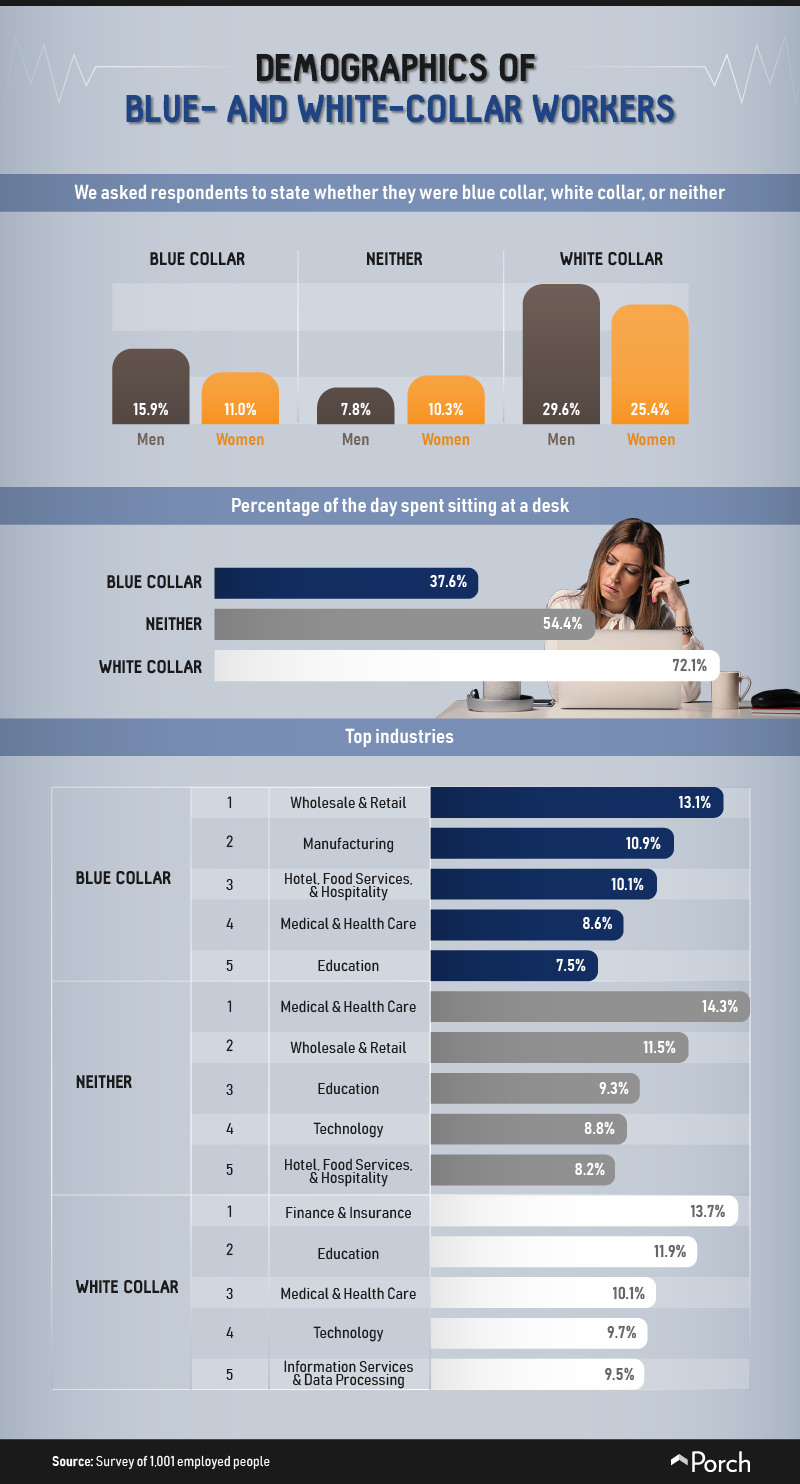

Among our respondents, a majority identified their jobs as white-collar professions. Blue-collar workers represented roughly 27 percent of those surveyed, and about 18 percent felt neither designation was appropriate. With regard to this uncertainty, it’s worth noting new technology has muddied the blue-white binary to some extent. Economists describe a recent rise in “new-collar” jobs, which demand technical training but no college degree. Our findings do suggest, however, that white-collar work remains associated with sedentary office culture. Those who deemed themselves white-collar professionals said they spent more than two-thirds of their workdays at a desk on average. Conversely, the most common industries for self-identified blue-collar workers were the wholesale and retail, manufacturing and hospitality fields—work typically performed on one’s feet.

Among our respondents, a majority identified their jobs as white-collar professions. Blue-collar workers represented roughly 27 percent of those surveyed, and about 18 percent felt neither designation was appropriate. With regard to this uncertainty, it’s worth noting new technology has muddied the blue-white binary to some extent. Economists describe a recent rise in “new-collar” jobs, which demand technical training but no college degree. Our findings do suggest, however, that white-collar work remains associated with sedentary office culture. Those who deemed themselves white-collar professionals said they spent more than two-thirds of their workdays at a desk on average. Conversely, the most common industries for self-identified blue-collar workers were the wholesale and retail, manufacturing and hospitality fields—work typically performed on one’s feet.

Feelings in the field

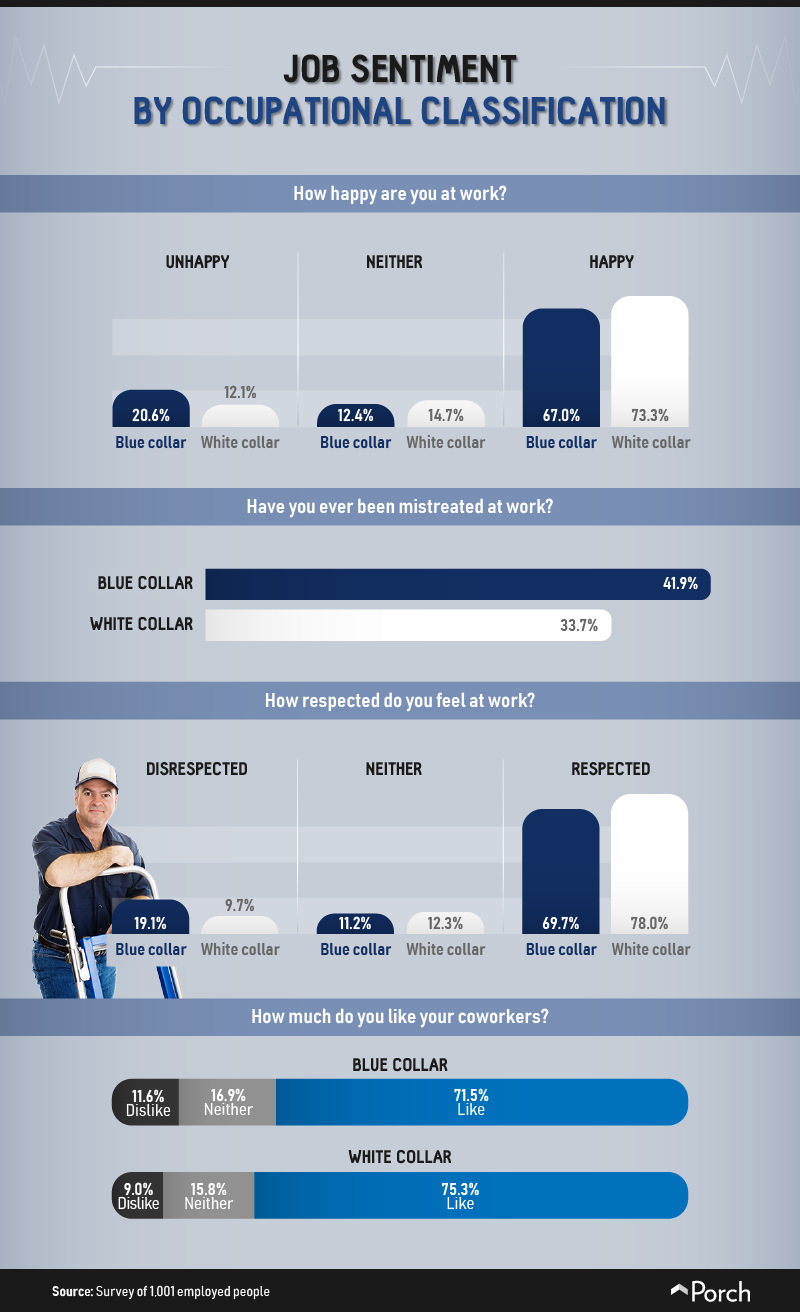

How does the job satisfaction of blue- and white-collar professionals compare? Whereas more than two-thirds of each cohort reported feeling happy at work, white-collar workers were slightly more likely to report as much. Likewise, blue-collar workers were more likely to express unhappiness about their professional lives. These findings resonate with global data gauging worker happiness, suggesting that individuals in labor-intensive positions experience positive emotions less frequently across the world. There may be many viable explanations for this happiness gap, but it seems unlikely to result from co-worker conflict. White-collar workers were only slightly more likely to express that they “liked” their colleagues. Our data do suggest, however, that poor treatment at work could contribute to the relative unhappiness of blue-collar workers. Indeed, blue-collar workers were substantially more likely to report being mistreated or disrespected at their jobs. Several studies have concluded that workers who feel respected in their roles experience better health and well-being. Could blue-collar workers’ happiness depend more on others’ civility than the actual nature of their work?

How does the job satisfaction of blue- and white-collar professionals compare? Whereas more than two-thirds of each cohort reported feeling happy at work, white-collar workers were slightly more likely to report as much. Likewise, blue-collar workers were more likely to express unhappiness about their professional lives. These findings resonate with global data gauging worker happiness, suggesting that individuals in labor-intensive positions experience positive emotions less frequently across the world. There may be many viable explanations for this happiness gap, but it seems unlikely to result from co-worker conflict. White-collar workers were only slightly more likely to express that they “liked” their colleagues. Our data do suggest, however, that poor treatment at work could contribute to the relative unhappiness of blue-collar workers. Indeed, blue-collar workers were substantially more likely to report being mistreated or disrespected at their jobs. Several studies have concluded that workers who feel respected in their roles experience better health and well-being. Could blue-collar workers’ happiness depend more on others’ civility than the actual nature of their work?

Fear of the future

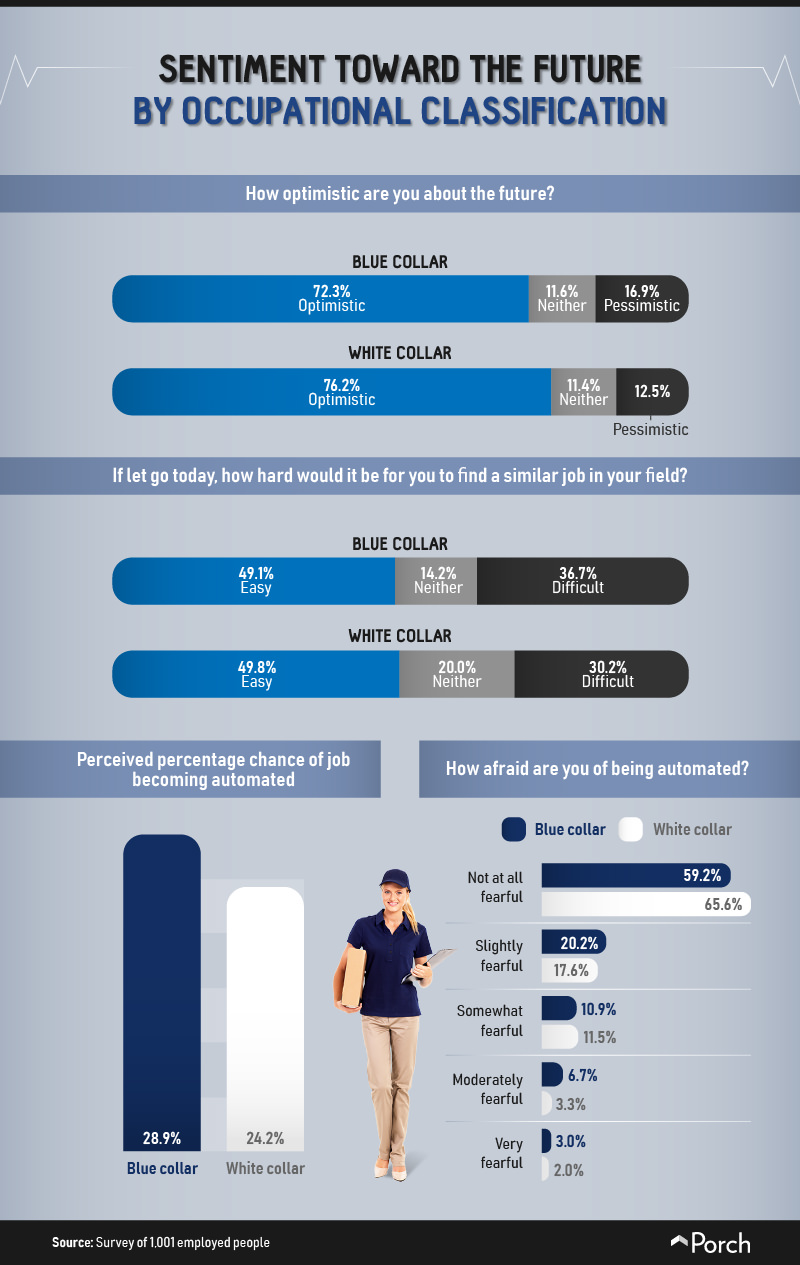

White-collar workers expressed slightly more optimism about the future than respondents in blue-collar roles. That sentiment could relate to the impending onslaught of automation; white-collar professionals were much less likely to fear replacement by machines. Still, some white-collar workers acknowledged there was a chance that automation could imperil their professions, with about a third expressing some degree of fear about the prospect. Their concerns may be justified: Experts predict automation will eventually encroach on even elite professions, such as medicine and law. Interestingly, roughly the same percentage of blue- and white-collar workers felt finding another job would be easy if they lost their current one. Nearly 37 percent of blue-collar workers said it would be difficult to do so, however, whereas just 30 percent of white-collar respondents said the same. Interestingly, blue-collar workers may actually have seen their job prospects improve most in recent months. America’s recent economic good fortune has actually occasioned a boom in blue-collar jobs, especially in sectors such as construction and manufacturing.

White-collar workers expressed slightly more optimism about the future than respondents in blue-collar roles. That sentiment could relate to the impending onslaught of automation; white-collar professionals were much less likely to fear replacement by machines. Still, some white-collar workers acknowledged there was a chance that automation could imperil their professions, with about a third expressing some degree of fear about the prospect. Their concerns may be justified: Experts predict automation will eventually encroach on even elite professions, such as medicine and law. Interestingly, roughly the same percentage of blue- and white-collar workers felt finding another job would be easy if they lost their current one. Nearly 37 percent of blue-collar workers said it would be difficult to do so, however, whereas just 30 percent of white-collar respondents said the same. Interestingly, blue-collar workers may actually have seen their job prospects improve most in recent months. America’s recent economic good fortune has actually occasioned a boom in blue-collar jobs, especially in sectors such as construction and manufacturing.

Professional gets personal

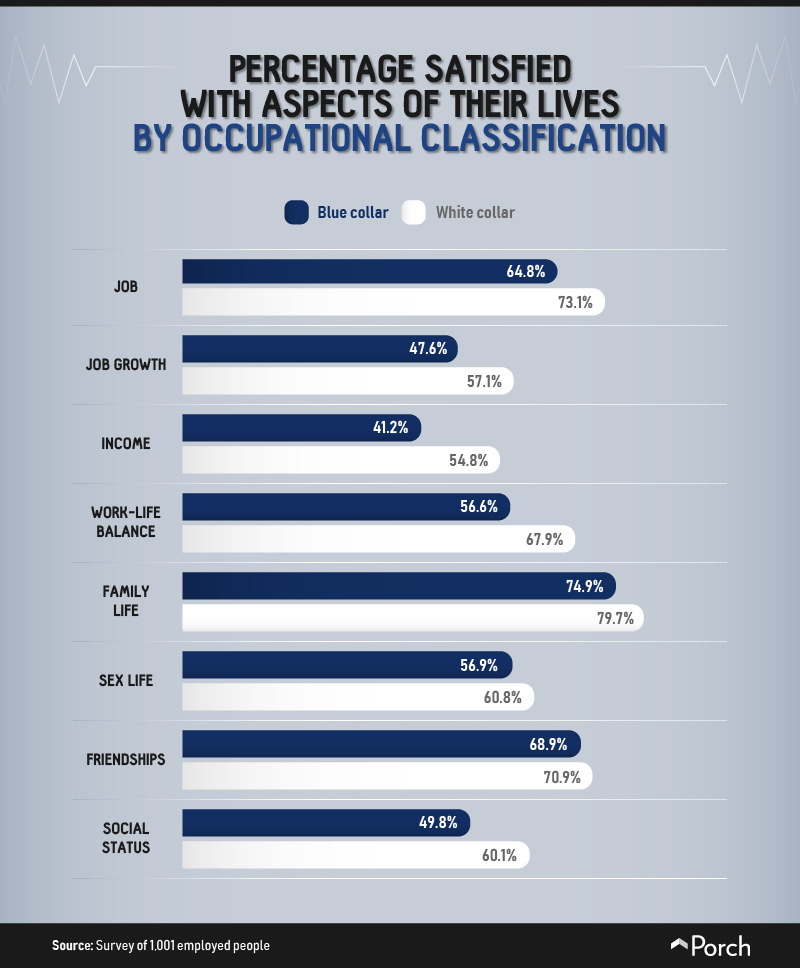

When we juxtaposed the satisfaction of white-collar and blue-collar workers concerning various aspects of their lives, white-collar workers tended to be more content across the board. But on some subjects, in particular, the differences were especially striking. Many of the greatest gaps emerged on matters directly concerning employment. Whereas nearly 55 percent of white-collar workers felt satisfied with their income, 41 percent of blue-collar workers said the same. Similar disparities were evident regarding their jobs, as well as their prospects for professional advancement. Life at home produced more modest gaps between blue- and white-collar cohorts, however. On the subjects of family, friendships, and sex, blue-collar satisfaction lagged less than five percentage points behind. Still, the percentage of blue-collar workers’ expressing satisfaction with their social status was 10 points lower than for white-collar respondents. Some suggest the “blue-collar values” of hard work and humility have been discounted in recent years, as America embraces more cosmopolitan social norms instead. But is that really the case?

When we juxtaposed the satisfaction of white-collar and blue-collar workers concerning various aspects of their lives, white-collar workers tended to be more content across the board. But on some subjects, in particular, the differences were especially striking. Many of the greatest gaps emerged on matters directly concerning employment. Whereas nearly 55 percent of white-collar workers felt satisfied with their income, 41 percent of blue-collar workers said the same. Similar disparities were evident regarding their jobs, as well as their prospects for professional advancement. Life at home produced more modest gaps between blue- and white-collar cohorts, however. On the subjects of family, friendships, and sex, blue-collar satisfaction lagged less than five percentage points behind. Still, the percentage of blue-collar workers’ expressing satisfaction with their social status was 10 points lower than for white-collar respondents. Some suggest the “blue-collar values” of hard work and humility have been discounted in recent years, as America embraces more cosmopolitan social norms instead. But is that really the case?

Class consciousness

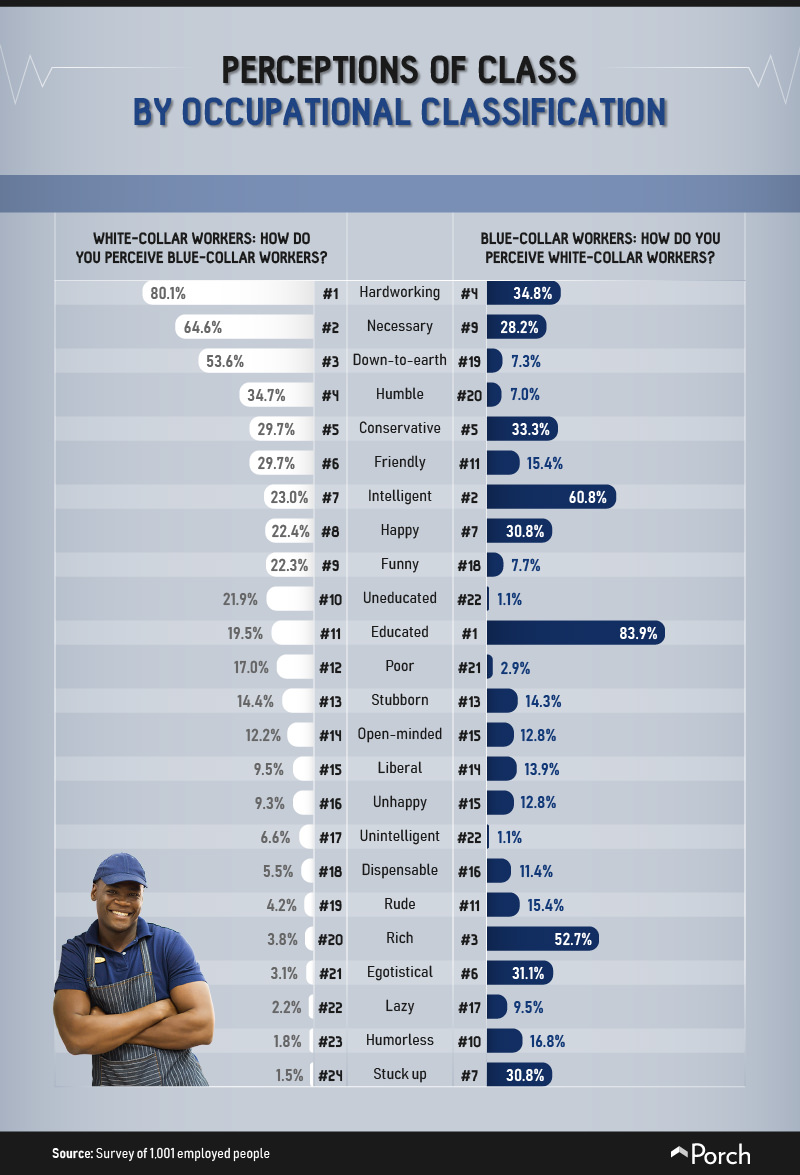

In sizing up white-collar individuals, blue-collar workers emphasized intellectual abilities. Nearly 84 percent perceived white-collar workers to be well-educated, and over 60 percent said they were intelligent. They also acknowledged a gap in wealth, with more than half of blue-collar workers calling white-collar workers rich. But negative connotations emerged as well: Roughly 3 in 10 blue-collar workers felt white-collar professionals were egotistical or stuck up. Fewer than 10 percent chose more positive descriptors, such as humble or funny. Conversely, white-collar workers seemed far more admiring of blue-collar individuals. Over 80 percent felt blue-collar people were hardworking, and a majority found them down-to-earth. Furthermore, fewer than 5% used harsh words to describe them, such as lazy, egotistical, or humorless. White-collar workers also perceived blue-collar workers as stubborn at the same rate as blue-collar workers perceived white collar (just over 14%). Why do blue-collar individuals typically perceive white-collar individuals more harshly? One possible explanation lies in our data about the mistreatment and disrespect that blue-collar workers experience at work. White-collar professionals may have great admiration for blue-collar workers, but that matters little if they treat them poorly in reality. As managers and customers, are white-collar individuals doing enough to demonstrate respect?

In sizing up white-collar individuals, blue-collar workers emphasized intellectual abilities. Nearly 84 percent perceived white-collar workers to be well-educated, and over 60 percent said they were intelligent. They also acknowledged a gap in wealth, with more than half of blue-collar workers calling white-collar workers rich. But negative connotations emerged as well: Roughly 3 in 10 blue-collar workers felt white-collar professionals were egotistical or stuck up. Fewer than 10 percent chose more positive descriptors, such as humble or funny. Conversely, white-collar workers seemed far more admiring of blue-collar individuals. Over 80 percent felt blue-collar people were hardworking, and a majority found them down-to-earth. Furthermore, fewer than 5% used harsh words to describe them, such as lazy, egotistical, or humorless. White-collar workers also perceived blue-collar workers as stubborn at the same rate as blue-collar workers perceived white collar (just over 14%). Why do blue-collar individuals typically perceive white-collar individuals more harshly? One possible explanation lies in our data about the mistreatment and disrespect that blue-collar workers experience at work. White-collar professionals may have great admiration for blue-collar workers, but that matters little if they treat them poorly in reality. As managers and customers, are white-collar individuals doing enough to demonstrate respect?

Education and eventual employment

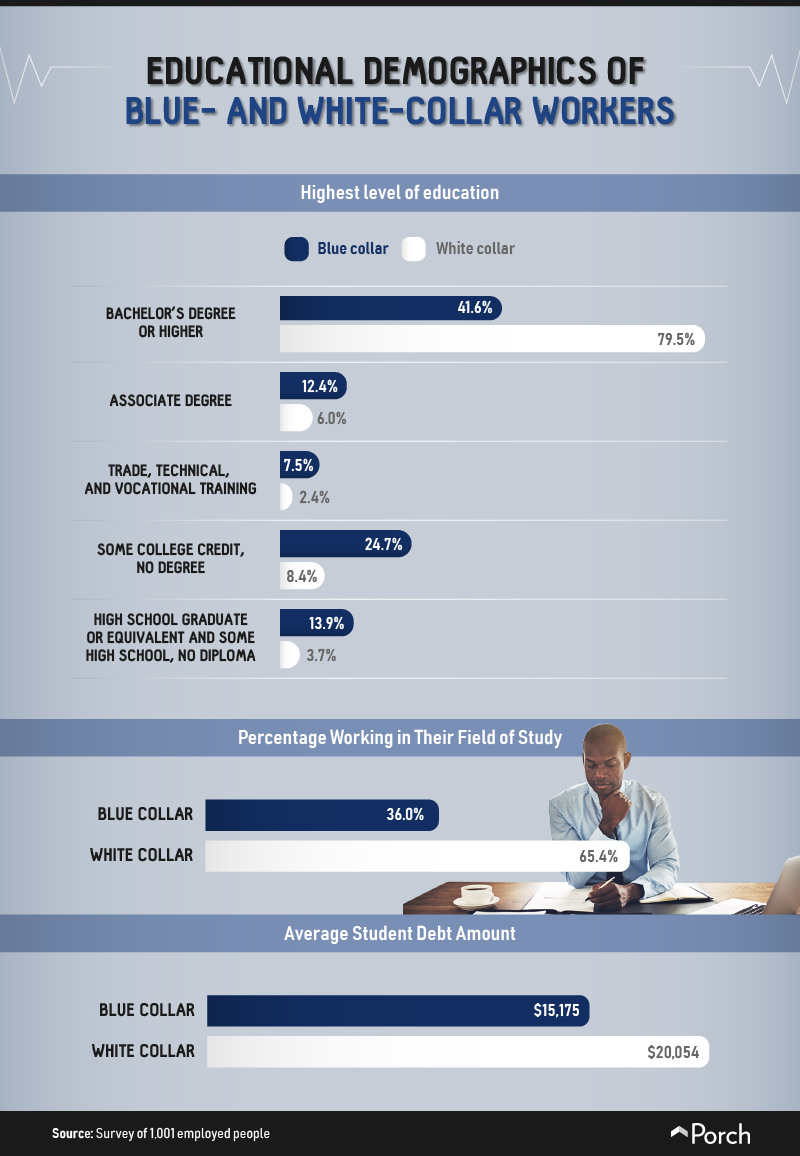

While nearly 4 in 5 white-collar workers had a bachelor’s degree, more than 40 percent of blue-collar individuals graduated from college as well. Blue-collar workers, by contrast, were more likely to hold an associate degree or have attended a trade school. Recently, policymakers have called for a resurgence of vocational schools to equip American workers to enter high-paying trades. Currently, blue-collar workers’ studies don’t often correspond to their careers: Just 36 percent said they worked in a field they had studied previously. Whatever they elected to study, blue-collar and white-collar employees paid dearly for the privilege. White-collar students had more than $20,000 in student loan debt on average, whereas blue-collar employees had a bit less. Unfortunately, even vocationally oriented schooling can leave students in crippling debt: Trucking school, for example, routinely costs thousands of dollars to attend.

While nearly 4 in 5 white-collar workers had a bachelor’s degree, more than 40 percent of blue-collar individuals graduated from college as well. Blue-collar workers, by contrast, were more likely to hold an associate degree or have attended a trade school. Recently, policymakers have called for a resurgence of vocational schools to equip American workers to enter high-paying trades. Currently, blue-collar workers’ studies don’t often correspond to their careers: Just 36 percent said they worked in a field they had studied previously. Whatever they elected to study, blue-collar and white-collar employees paid dearly for the privilege. White-collar students had more than $20,000 in student loan debt on average, whereas blue-collar employees had a bit less. Unfortunately, even vocationally oriented schooling can leave students in crippling debt: Trucking school, for example, routinely costs thousands of dollars to attend.

Obtaining ownership

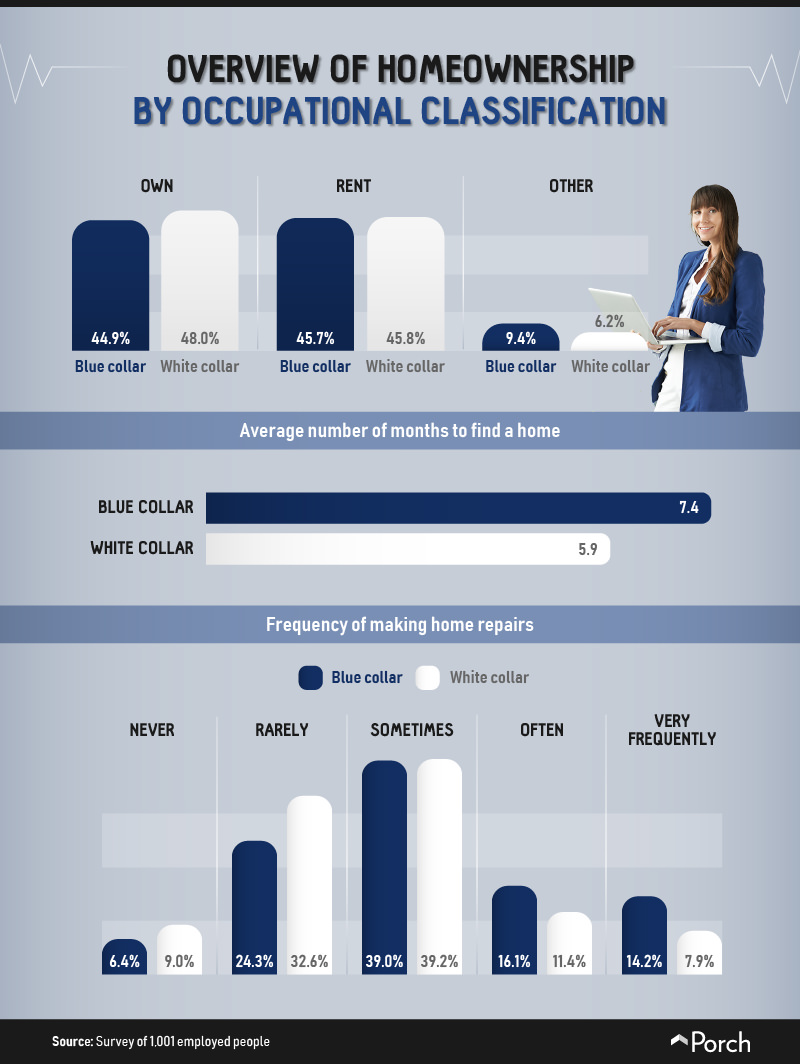

Homeownership has long been perceived as an integral part of the American Dream. But for a majority of blue- and white-collar workers, owning a home was not yet a reality. White-collar workers were more likely to be homeowners, but only slightly so. Those who did own property had an easier time finding a home than their blue-collar peers, however. Blue-collar workers required more than seven months on average; white-collar respondents needed less than six. Because many home improvement professions are typically regarded as blue-collar gigs, one might assume blue-collar workers were more willing to make their own repairs around the home. This was true to some extent, although white-collar workers weren’t entirely opposed to getting their hands dirty either. Whereas 14 percent of blue-collar workers frequently performed repairs around the house, less than 8 percent of white-collar workers said the same.

Homeownership has long been perceived as an integral part of the American Dream. But for a majority of blue- and white-collar workers, owning a home was not yet a reality. White-collar workers were more likely to be homeowners, but only slightly so. Those who did own property had an easier time finding a home than their blue-collar peers, however. Blue-collar workers required more than seven months on average; white-collar respondents needed less than six. Because many home improvement professions are typically regarded as blue-collar gigs, one might assume blue-collar workers were more willing to make their own repairs around the home. This was true to some extent, although white-collar workers weren’t entirely opposed to getting their hands dirty either. Whereas 14 percent of blue-collar workers frequently performed repairs around the house, less than 8 percent of white-collar workers said the same.

What you do—and what you don’t have to

Our results suggest many workers feel great strain related to their employment, both in terms of the present nature of their jobs and their financial security in the years to come. Although these concerns raise significant structural challenges, meaningful improvement may be possible on an interpersonal level. Whether we choose to be more thoughtful in our communication with co-workers or more patient in our interactions with those providing some service, we can ease the burden of negative feelings for others at work. In fact, we may even find practicing kindness helps alleviate our own feelings of unhappiness at times. No matter your profession, you likely value the time you spend away from work. Finding time to relax can be essential to remaining productive and happy in your personal and professional endeavors. Don’t let an endless list of home improvement chores keep you from catching a break. With a little help from our team at Porch, you can find qualified professionals to tackle any project, all at a reasonable rate. Whether you’re looking for carpentry , landscaping, or even tv mounting, we can help you achieve all your home improvement goals. Explore our project cost guides and free quotes today to see just how little work you’ll need to do.

Methodology

We surveyed 1,001 full-time employed people about their jobs, job satisfaction, and experiences on and off the clock. Our respondents identified as 55 percent white collar, 27 percent blue collar, and 18 percent as neither. All respondents were surveyed through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. To avoid making judgment calls on people’s day-to-day activities and their industries, we asked people to determine what “collar” they fell into. Because our data rely on self-reporting, we are trusting individual respondents on their perceptions. Additionally, the Mechanical Turk population may be skewed toward certain demographics, such as white-collar workers, though every effort has been made to normalize any inconsistencies in sampling.

Fair Use Statement

Feel free to share our graphics and findings with your own audience online for noncommercial purposes. If you do, simply include a link to this page to attribute our team for our efforts. No matter the color of your collar, getting due credit feels pretty good.