Stop in the name of love? More like go. Nearly 36 million Americans move every year, and not all of them are single. Romantic choices must be made to either nurture or end relationships, especially when a partner has a job opportunity away from home. Moving to a new workplace, new city, or a new home can be scary, but it can be even scarier if your significant other doesn’t come with you. So what if the love of your life were to receive a dream job across the country—would you go with them? What about in a neighboring state? Or even across the world? We asked 700 people for their reaction to certain moving situations, as well as 300 respondents about the choices they ultimately made for their career and love life. Continue reading to see how career moves can impact American romance.

In the mind of a move

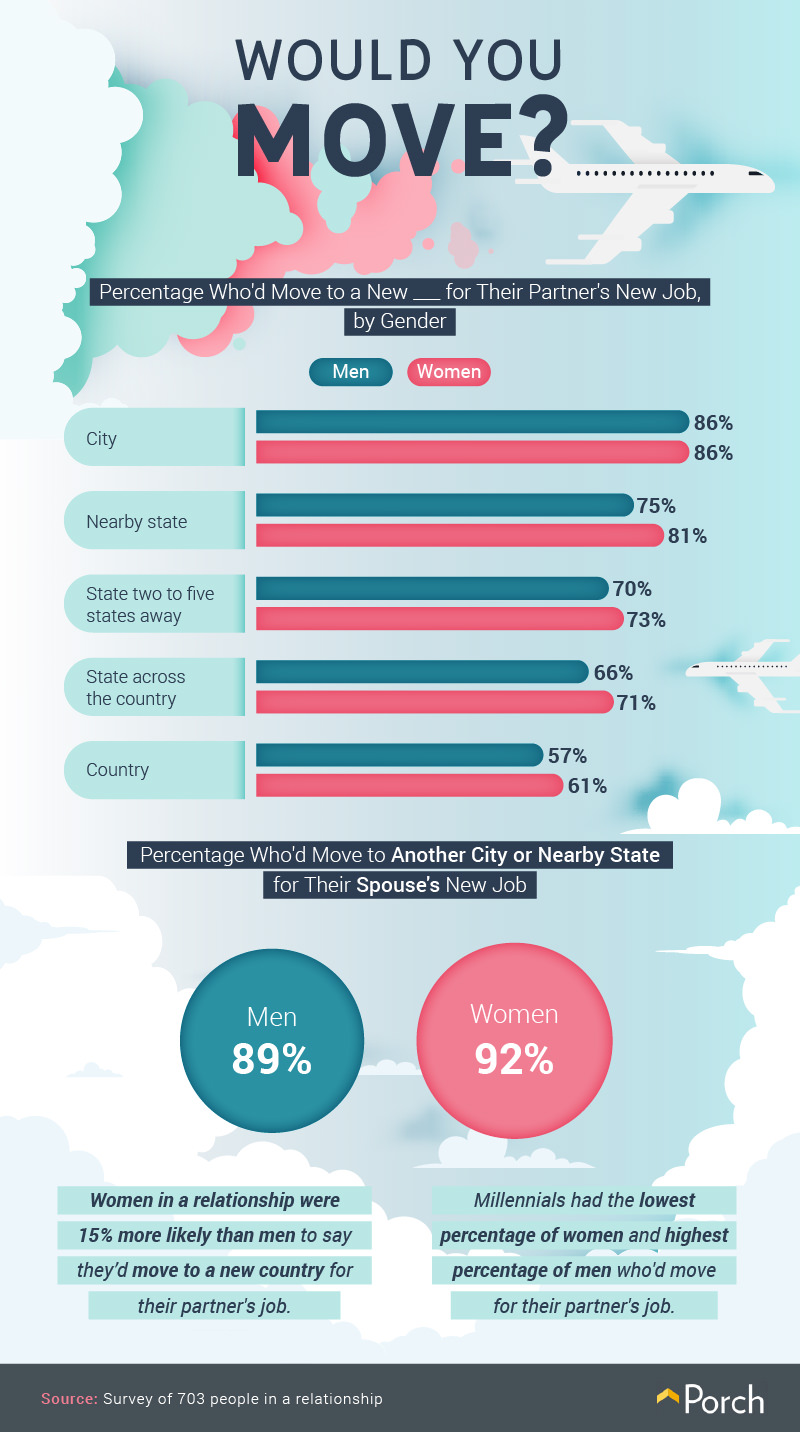

Aside from moving to a new city, women were consistently more willing than men to move for their partner’s career. Eighty-one percent of women were willing to move to a nearby state (75 percent for men), 71 percent across the country (66 percent for men), and 61 percent to a new country (57 percent for men). Why the adaptability for women? It could be because, despite progress in the workforce gender gap, women continue to stay home more than men. If a woman (and possibly her family) relies on her partner’s income, it may feel like a clear choice to move for their partner’s career. Men, on the other hand, may be more reluctant to leave their own job, even if their partner was offered an opportunity elsewhere. However, millennials had the lowest percentage of women who were willing to move for their partner’s career. This generation of women is pouring into the workforce. Perhaps their decreased willingness to relocate reflects an increased interest in maintaining their own career. As one would guess, though, the firmest of relationship commitments—marriage—left respondents quite willing to move for their partner’s career. Eighty-nine percent of married men and 92 percent of married women were willing to move with their spouse for a professional relocation.

Aside from moving to a new city, women were consistently more willing than men to move for their partner’s career. Eighty-one percent of women were willing to move to a nearby state (75 percent for men), 71 percent across the country (66 percent for men), and 61 percent to a new country (57 percent for men). Why the adaptability for women? It could be because, despite progress in the workforce gender gap, women continue to stay home more than men. If a woman (and possibly her family) relies on her partner’s income, it may feel like a clear choice to move for their partner’s career. Men, on the other hand, may be more reluctant to leave their own job, even if their partner was offered an opportunity elsewhere. However, millennials had the lowest percentage of women who were willing to move for their partner’s career. This generation of women is pouring into the workforce. Perhaps their decreased willingness to relocate reflects an increased interest in maintaining their own career. As one would guess, though, the firmest of relationship commitments—marriage—left respondents quite willing to move for their partner’s career. Eighty-nine percent of married men and 92 percent of married women were willing to move with their spouse for a professional relocation.  Men were 23 percent more likely than women to say they cared more about meeting their own career goals than their significant other’s. Playing the devil’s advocate, this may reflect more of a desire to maintain the status quo than a me-before-you mindset. If they currently support a relationship or family, their own career goals may be more important than the potential career goals of their partner. Fortunately, for millennials and future generations, these career gender gaps may shift even more, and with them, the status quo.

Men were 23 percent more likely than women to say they cared more about meeting their own career goals than their significant other’s. Playing the devil’s advocate, this may reflect more of a desire to maintain the status quo than a me-before-you mindset. If they currently support a relationship or family, their own career goals may be more important than the potential career goals of their partner. Fortunately, for millennials and future generations, these career gender gaps may shift even more, and with them, the status quo.

And then what happened?

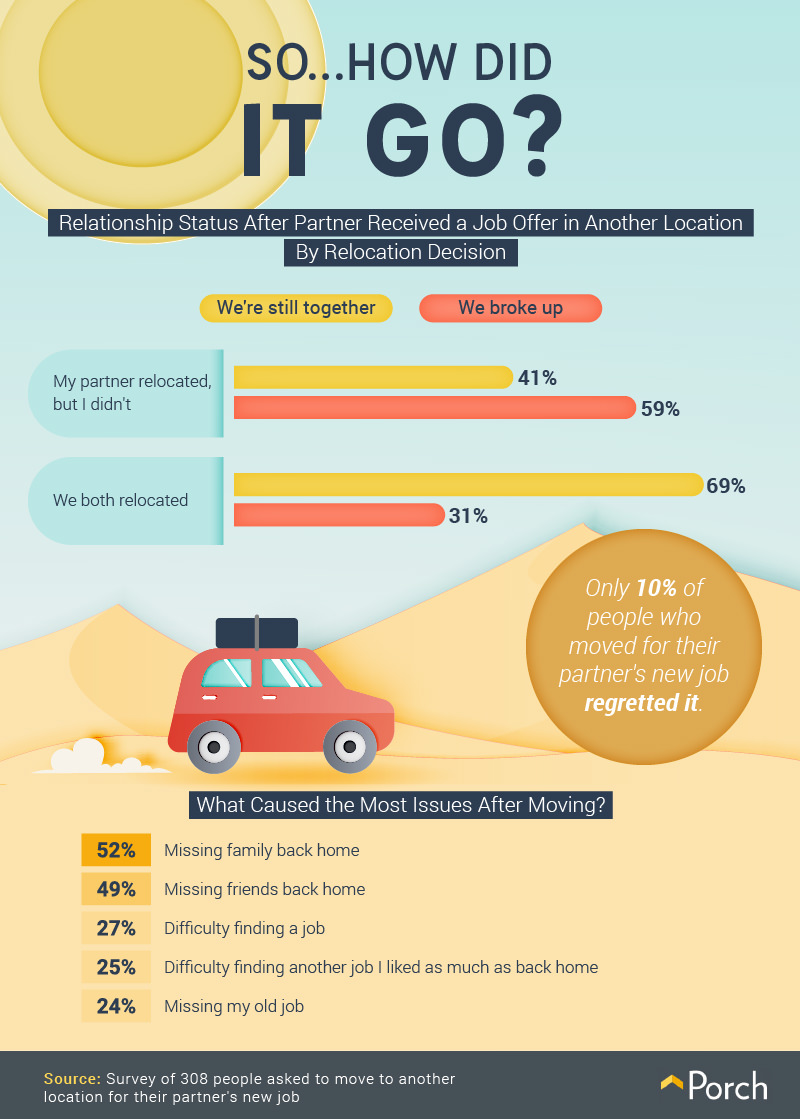

At the risk of bearing bad news, the odds are against you and your partner if one of you stays while the other relocates. Fifty-nine percent of people broke up after only one partner moved for a job. That said, there’s no guarantee of staying together even if you do move as a team. Even after one person accepted a job offer and their significant other moved with them, 31 percent of respondents still ended their relationship. Nevertheless, only 10 percent of people who moved for their partner’s job regretted it. Even in the face of a breakup, many may resist regretting a major life decision. However difficult the past may have been, it brought you to where you are today. Ultimately, this is an argument for living without regret, even when mistakes are made. When couples did move together, though, the biggest issue wasn’t the relationship or job itself—it was missing family and friends. The biggest issue of relocating for a job was missing family, which was mentioned by 52 percent of respondents. Another 49 percent missed their friends.

At the risk of bearing bad news, the odds are against you and your partner if one of you stays while the other relocates. Fifty-nine percent of people broke up after only one partner moved for a job. That said, there’s no guarantee of staying together even if you do move as a team. Even after one person accepted a job offer and their significant other moved with them, 31 percent of respondents still ended their relationship. Nevertheless, only 10 percent of people who moved for their partner’s job regretted it. Even in the face of a breakup, many may resist regretting a major life decision. However difficult the past may have been, it brought you to where you are today. Ultimately, this is an argument for living without regret, even when mistakes are made. When couples did move together, though, the biggest issue wasn’t the relationship or job itself—it was missing family and friends. The biggest issue of relocating for a job was missing family, which was mentioned by 52 percent of respondents. Another 49 percent missed their friends.

Relocation hesitation

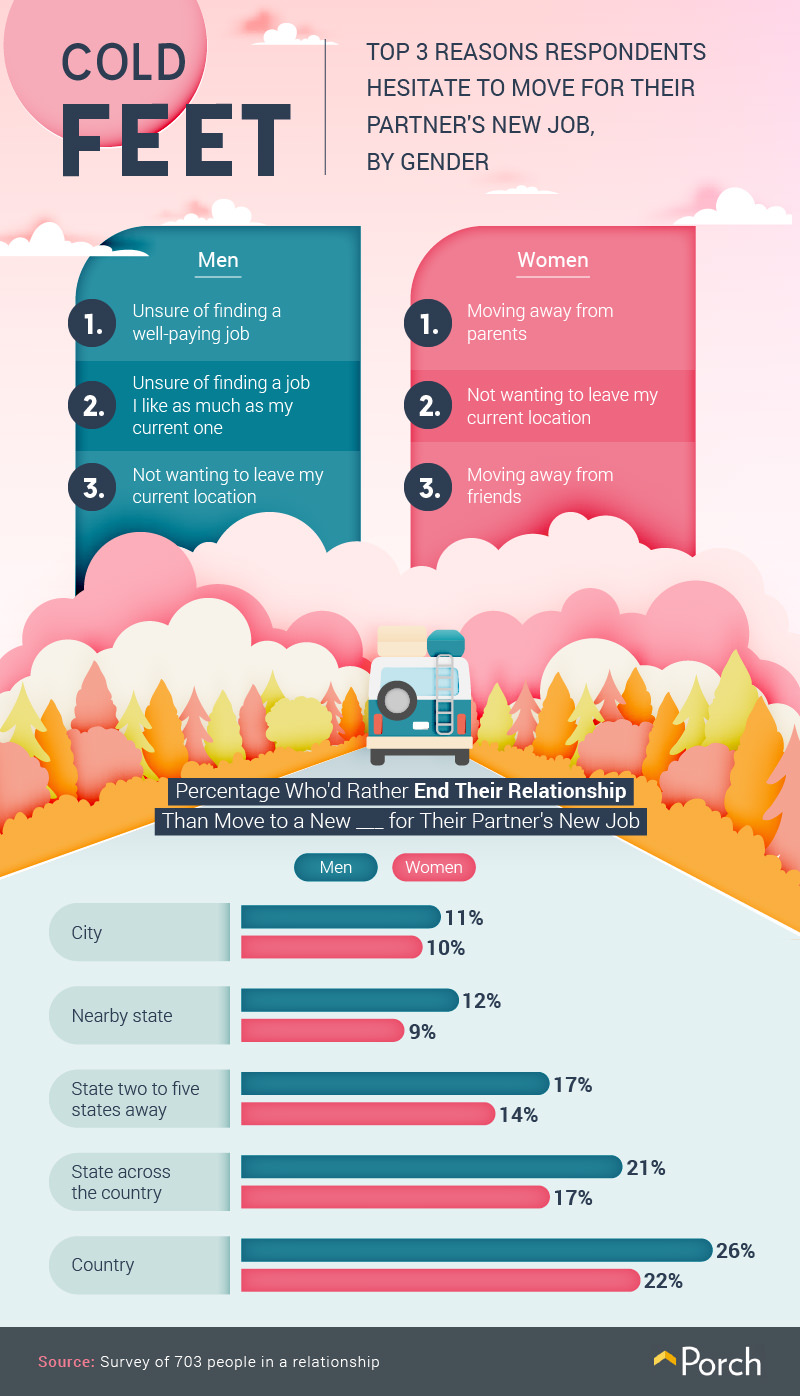

Deciding to stay with your partner through relocation may have to do with more than just the strength or intensity of the relationship. Other important relationships, like those with your friends, family, and even home, all carry weight when moving for someone else’s career. Women’s top concern was moving away from their parents. However, this probably isn’t just about missing mom and dad. Women are much more likely than men to care for their aging parents. In fact, 2 in 3 caregivers are women. Men, however, mentioned neither friends nor family when explaining why they were hesitant to move for their partner’s job. Instead, they were most likely to mention uncertainty about finding a new job or even one they liked. These concerns may even have something to do with men’s increased likelihood of ending their relationship rather than moving for their partner’s career.

Deciding to stay with your partner through relocation may have to do with more than just the strength or intensity of the relationship. Other important relationships, like those with your friends, family, and even home, all carry weight when moving for someone else’s career. Women’s top concern was moving away from their parents. However, this probably isn’t just about missing mom and dad. Women are much more likely than men to care for their aging parents. In fact, 2 in 3 caregivers are women. Men, however, mentioned neither friends nor family when explaining why they were hesitant to move for their partner’s job. Instead, they were most likely to mention uncertainty about finding a new job or even one they liked. These concerns may even have something to do with men’s increased likelihood of ending their relationship rather than moving for their partner’s career.

This better be worth it

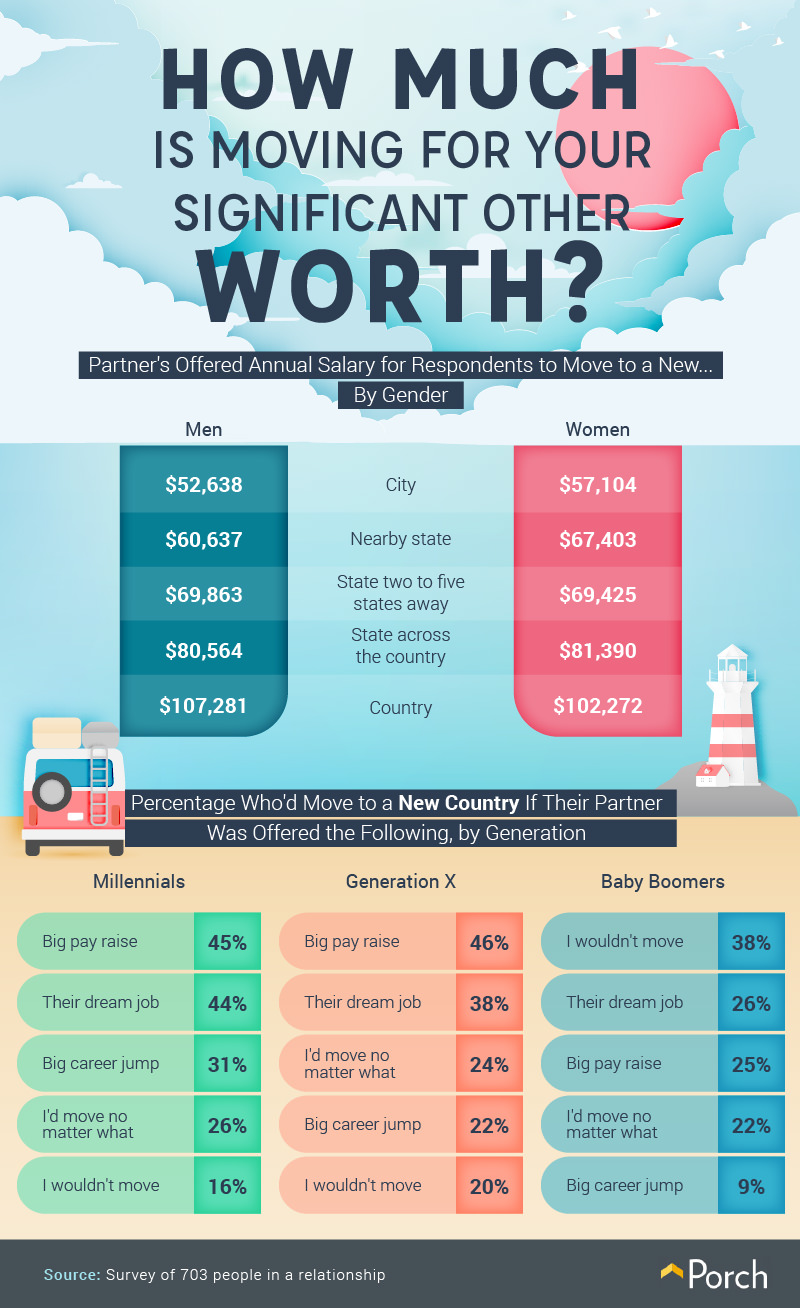

An interstate move, on average, costs $4,300, but the average American would require much more to relocate for their significant other’s job. On average, men wanted their partner’s annual salary to be at least $52,638 when moving to a new city and $80,564 to move across the country. For women, these numbers were relatively similar: $57,104 and $81,390, respectively. The adventurer in you may dream of moving to another country with your partner. However, both men and women expected to be offered at least six figures to move outside of the U.S. And as respondents aged, they became even less willing to leave the country for a partner’s job: 38 percent of baby boomers agreed that no amount of money or profession would make them move to a new country, compared to just 16 percent of millennials and 20 percent of Gen Xers.

An interstate move, on average, costs $4,300, but the average American would require much more to relocate for their significant other’s job. On average, men wanted their partner’s annual salary to be at least $52,638 when moving to a new city and $80,564 to move across the country. For women, these numbers were relatively similar: $57,104 and $81,390, respectively. The adventurer in you may dream of moving to another country with your partner. However, both men and women expected to be offered at least six figures to move outside of the U.S. And as respondents aged, they became even less willing to leave the country for a partner’s job: 38 percent of baby boomers agreed that no amount of money or profession would make them move to a new country, compared to just 16 percent of millennials and 20 percent of Gen Xers.

Making money moves

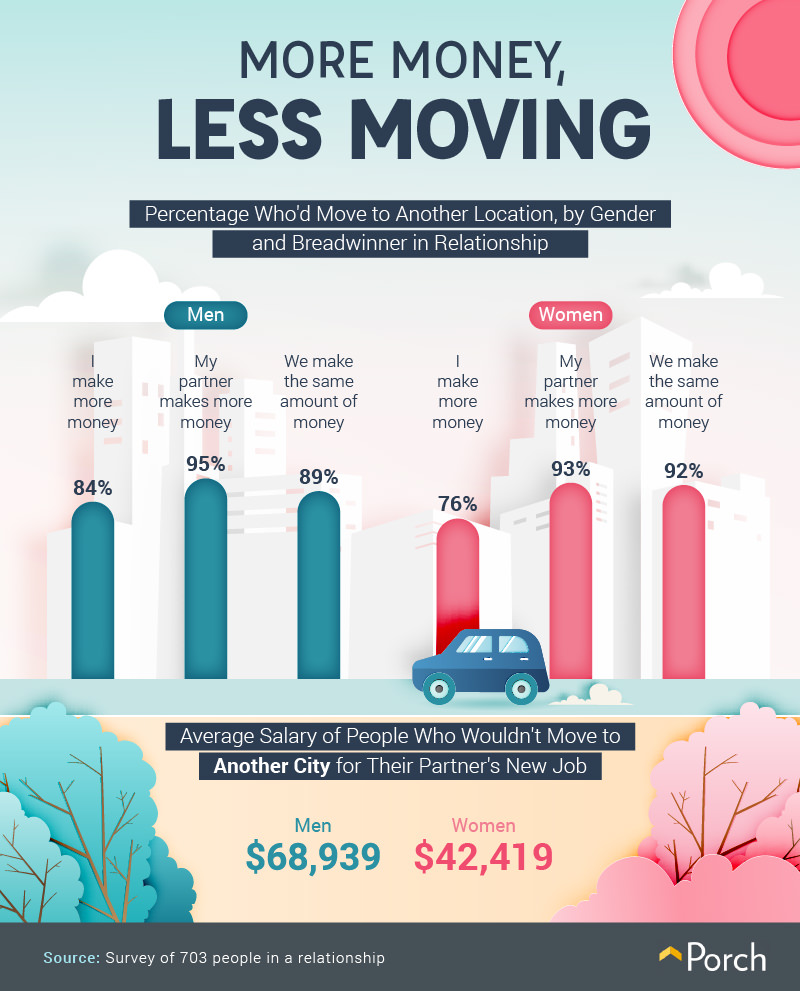

Women who made more money than their partner were actually less likely than male breadwinners to move for a partner’s job. For those who made the same amount or less than their partner, though, men and women were similarly ready to move for the other’s job. Of those who refused to move no matter what, men made more. On average, men who wouldn’t move to a new city for their partner made $68,939 each year, compared to women who earned just $39,874 annually. In other words, men required more financial motivation than women to stay put. Maybe this is another contributor to the persisting gender wage gap.

Women who made more money than their partner were actually less likely than male breadwinners to move for a partner’s job. For those who made the same amount or less than their partner, though, men and women were similarly ready to move for the other’s job. Of those who refused to move no matter what, men made more. On average, men who wouldn’t move to a new city for their partner made $68,939 each year, compared to women who earned just $39,874 annually. In other words, men required more financial motivation than women to stay put. Maybe this is another contributor to the persisting gender wage gap.

Romance in moving

To move or not to move? That is the question—well, it may be if your significant other happens to get a job offer out of town. For most women, the answer was move. And for most men? Move as well, just not as often. However, men were more likely to end their relationship than relocate for their partner’s career. New cities, states, and jobs may just go hand in hand with new relationships. Possible breakups aside, career opportunities are important enough to discuss openly with your partner. Maybe they will be more open to a new city or country than you think. And if not, it’s beneficial to have that information before a job opportunity presents itself. This way, you can make the best possible decision for both your romantic and professional life. If you do decide to move, equip yourself and your partner with the tools you’ll need to thrive in any location. You’ll certainly have questions about your new home and where to turn for home improvement. For any type of question, concern, or idea, visit Porch for well-trained experts in your area.

Methodology and limitations

We used Amazon’s Mechanical Turk to survey 703 people in a relationship and 308 people who decided whether to move for their significant other’s job. Responses were gathered from two separate surveys for each of these groups. Of the 703 respondents in a relationship, 39 percent were married; 31 percent were in a relationship; 5 percent were engaged; 5 percent were divorced and in a relationship; and 1 percent were divorced and remarried. Of all respondents, 54 percent were women; 46 percent were men; and less than 1 percent identified with a nonbinary gender. Fifty-seven percent of respondents were millennials (born 1981 to 1997); 30 percent were from Generation X (born 1965 to 1980); 11 percent were baby boomers (born 1946 to 1964); 2 percent were from Generation Z (born 1928 to 1943); and less than 1 percent were from the silent generation (born 1928 to 1945). The average age of respondents was 38 with a standard deviation of 12 years. To be considered in our data, respondents were required to a) complete all survey questions and b) pass an attention-check question in the middle of the survey. Participants who failed to do either of these were excluded from the study. In the visualizations where a specific location was not specified (e.g., city, state, or country), responses were grouped. For analysis of quantitative values, outliers were moved so that findings could not be exaggerated. A limitation of this study is that we utilized self-reported data. This method may include side effects of selective memory, exaggeration, attribution, and telescoping. However, we made sure our survey questions were objective and unbiased. We also did not perform any statistical testing on the data, and all claims are based on means alone. This study is intended for entertainment use only, and future research should approach this topic in a more academic and rigorous manner

Fair use statement

Moving for a loved one? Or know someone who is? You’re welcome to share this article for noncommercial purposes about how it played out for other Americans. Just be sure to link back to this page and its authors so that they can receive proper credit for their work.